In the high-stakes world of digital secrecy, we are currently living on borrowed time. Most of our modern security – from banking transactions to private messages – relies on computational security. We assume that certain mathematical problems, like factoring massive integers, are just “too hard” for computers to solve.

But as quantum computing moves from theory to reality, these “hard” problems are destined to become easy. The BB84 protocol, proposed by Charles Bennett and Gilles Brassard in 1984, offers the antidote. It shifts the foundation of secrecy from the complexity of math to the fundamental laws of physics.

Hard to Break vs. Impossible to Break

To understand why BB84 is revolutionary, we must distinguish between the two tiers of cryptographic security.

"Hard to Break" (The Classical Standard)

Current systems like RSA are based on mathematical difficulty. If it takes a supercomputer 10,000 years to crack a code, we call it “secure.” However, this security is conditional. It assumes the attacker has limited computing power and that no one discovers a mathematical “shortcut.” If a powerful quantum computer is built, these codes aren’t just “hard” to break; they are effectively broken instantly.

"Impossible to Break" (The Quantum Standard)

BB84 strives for information-theoretic security. This means that even an attacker with infinite computing power cannot break the code. The security is derived from the One-Time Pad (OTP). In an OTP system, the key is truly random, as long as the message, and used only once. If Alice and Bob can share such a key securely, their communication becomes mathematically impossible to decrypt. BB84 is the mechanism that makes this secure key exchange possible.

The Mechanics of Light: Photon Polarization

The “magic” of BB84 lies in photon polarization. Imagine light as a wave vibrating in a specific direction. Alice uses individual particles of light “photons” to carry her secret bits.

Alice’s Encoding: Setting the State

For Alice to “encode” a bit, she doesn’t just pick a number; she physically sets the state of a photon by passing it through a polarization filter. This filter acts as a gate that only allows light vibrating in a specific orientation to pass through, effectively “setting” the photon’s quantum state.

The Secret Ingredient: Photon Polarization

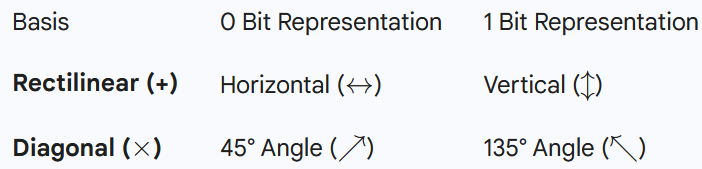

The BB84 protocol uses photons –individual particles of light. These photons have a property called polarization, which refers to the direction in which the light waves vibrate.

- Rectilinear Basis (+): Includes Horizontal (0°) and Vertical (90°) filters.

- Diagonal Basis (×): Includes 45° and 135° filters.

Quantum Memory: The Certainty of Alignment vs. The Chaos of Mismatch

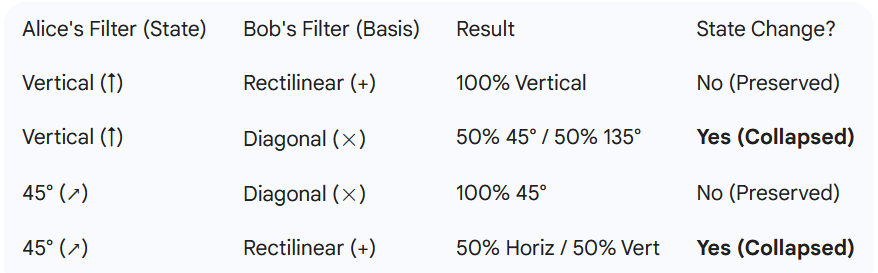

A defining characteristic of the BB84 protocol is how the act of measurement interacts with a photon’s “memory.” When Alice passes a photon through her initial filter, she sets its state. From that point on, the photon’s behavior is dictated by how its current state aligns with the next “apparatus” it encounters.

- The Power of Alignment: 100% Determinism If the subsequent measurement uses the exact same basis as the previous one, the outcome is entirely deterministic. Think of it as a physical lock and key: if Alice sends a Vertical photon (↕) and Bob uses a Vertical filter, the photon passes through with 100% certainty. More importantly, the photon remains in that Vertical state. You could measure it a thousand times in that same basis, and as long as the filters remain aligned, you will receive the exact same “1” bit every single time.

- The Cost of Mismatch: The Probabilistic Collapse The “quantum weirdness” begins when the filter apparatus is not aligned with the photon’s current state. If a Vertical photon (↕) encounters a Diagonal filter (×), it can no longer rely on its “Vertical” identity. Because the Diagonal basis is rotated 45° relative to the Rectilinear basis, the photon is forced to “choose” a new orientation to fit through the new apparatus.

- The 50/50 Split: The photon has a 50% probability of being detected as 45° (↗) and a 50% probability of being detected as 135° (↖).

- State Erasure: Crucially, once this measurement occurs, the photon’s “memory” of being Vertical is wiped. It has collapsed into a new state. If you were to try and measure that same photon again using the original Rectilinear filter, it would now be a 50/50 coin toss whether it shows up as Vertical or Horizontal.

The Eavesdropper’s Catch-22: This is why Eve cannot “peek” without consequences. If she intercepts a photon and uses the wrong filter, she doesn’t just get a random bit – she physically alters the photon. When that altered photon finally reaches Bob, even if Bob uses the correct filter (the one Alice used), the “memory” of Alice’s original state has already been destroyed by Eve’s interference, leading to the detectable errors that expose her presence.

Crucially: Once the photon passes through Bob’s Diagonal filter, its original “Vertical” identity is destroyed. It has collapsed into a new state.

The BB84 Key Exchange: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Alice and Bob use these properties to build a secret key over a “Quantum Channel” (like a fiber optic cable) while chatting about their process over a “Public Classical Channel” (like the internet).

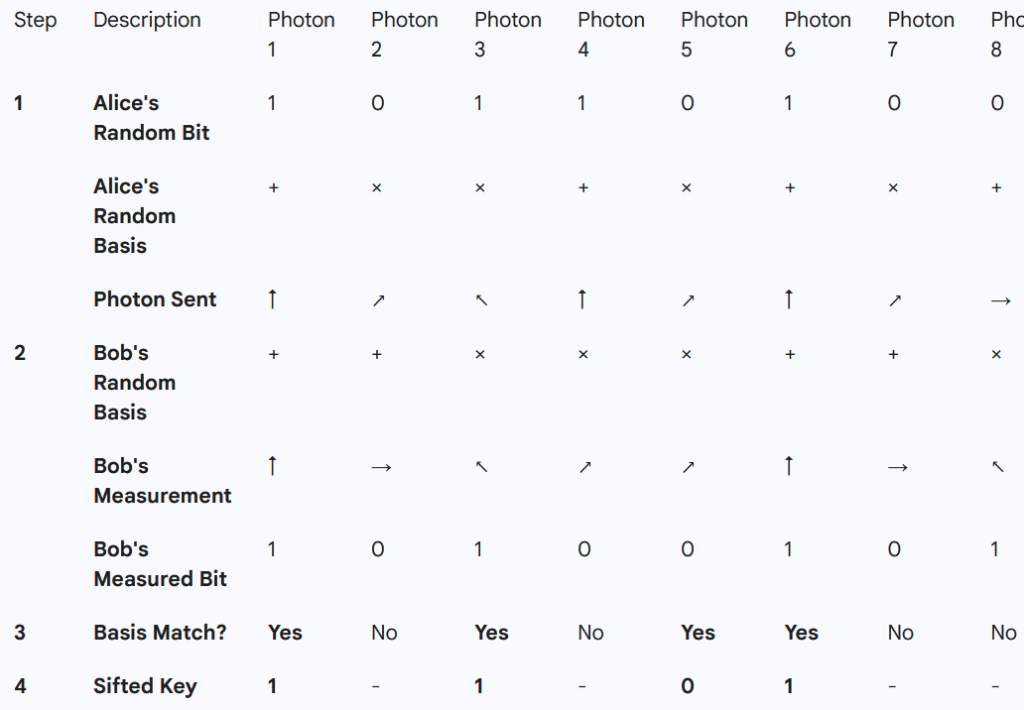

- Transmission: Alice generates a random string of bits (0s and 1s). For each bit, she randomly chooses a basis (+ or ×) and sends a polarized photon to Bob.

- Measurement: Bob doesn’t know Alice’s bases. He randomly chooses a basis for each incoming photon and records his result.

- The Reveal (Sifting): Alice and Bob talk on the public channel. They tell each other which basis they used for each photon (e.g., “For photon #1, I used Rectilinear”). They never reveal the actual bit value.

- Key Matching: * If their bases matched, they keep that bit (it’s deterministic!). If their bases didn’t match, they discard the bit (it was probabilistic/random).

- Error Check: They compare a small, random subset of their kept bits. If they match perfectly, they know no one was listening.

The Eavesdropper’s Dilemma: Why Eve Fails

If an eavesdropper, Eve, tries to intercept the photons, she faces a physical impossibility.

The "Measure-and-Resend" Trap

Eve cannot simply “copy” a photon due to the No-Cloning Theorem. To know the bit Alice sent, Eve must measure the photon. But Eve doesn’t know the correct basis!

- If she uses the wrong basis, she changes the photon’s state (collapse).

- When she sends her “measured” photon to Bob, she will be sending the wrong state 50% of the time.

- This introduces a 25% error rate into Alice and Bob’s final key. Alice and Bob will see these errors during their “Error Check” and realize someone is tapping the line.

The "Too Late" Factor

Eve might think she can record the photons and wait for Alice and Bob to announce the bases on the public channel. She can’t. Quantum states cannot be “recorded” or “stored” without being measured. By the time Alice reveals that she used a 45° filter, the photon has already hit Bob’s detector. Eve is left with the realization that she should have used a Diagonal filter, but the photon is already gone. Knowledge of the filter orientation arrives far too late to intercept the original state.

The Final Shield: XOR and the One-Time Pad

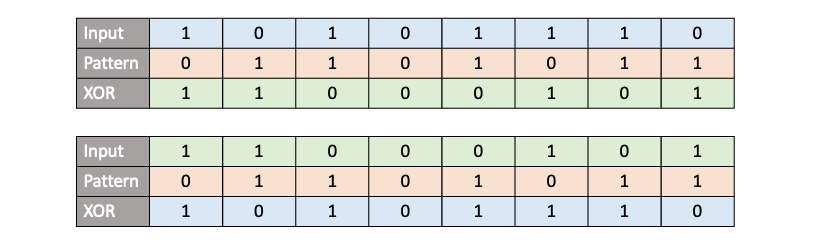

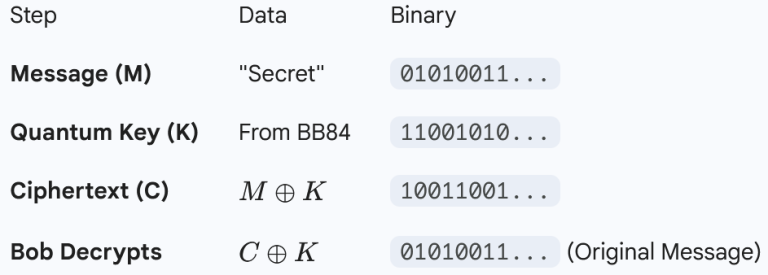

Once Alice and Bob have their shared, secret, and identical key (the bits where their bases matched), they use it to encrypt their actual message using the XOR (⊕) operation.

How XOR Works

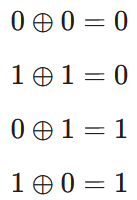

The XOR operation is a binary logic gate where the output is 1 only if the inputs are different:

Encryption and Decryption

To encrypt a message (M) with a key (K), Alice calculates the ciphertext (C):

To decrypt, Bob simply XORs the ciphertext with the same key:

Because the key K was generated via the random quantum process of BB84 and is only used once, the ciphertext C contains zero information about the message without the key. It looks like pure, random noise.

The bitwise XOR has a incredible feature ‘involution‘ which means the function is an inverse of itself. So if we have an input bit array, and we apply a XOR operation to it with a key, we get an output. Now if we take the output and XOR it with the original key again, we get back the input. This bidirectional nature makes it convenient for cipher algorithms.

Because the key was generated by quantum randomness and used only once (One-Time Pad), the ciphertext is mathematically unbreakable. Even if Eve has the ciphertext, without the exact quantum key, it is just random noise.

Conclusion

The BB84 protocol is a masterclass in using the “weirdness” of the universe to our advantage. By forcing an attacker to choose between ignorance or detection, it creates a communication channel that doesn’t just resist cracking – it renders cracking physically impossible. In a future where computers can solve any math problem, our secrets will remain safe, not because our math is better, but because we’ve harnessed the fundamental nature of light itself.

Cheers – Amit Tomar!!