In the world of cryptography, the One-Time Pad (OTP) is the only mathematically “perfect” encryption. It requires a key that is truly random, as long as the message, and – most importantly – never reused. The moment you reuse that key, you aren’t using a One-Time Pad anymore; you’re using a Many-Time Pad. It doesn’t matter if your key is 4096 bits of high-entropy noise. If that noise is the same for Message A and Message B, the noise cancels itself out, leaving your private data standing naked in the wind.

When you use a short shared secret and repeat it to encrypt a longer message – a method often called a repeating-key XOR cipher – you aren’t building a vault; you’re building a screen door. Here is a deep dive into why this happens and how we can systematically tear it apart.

The Logic of the XOR Operation

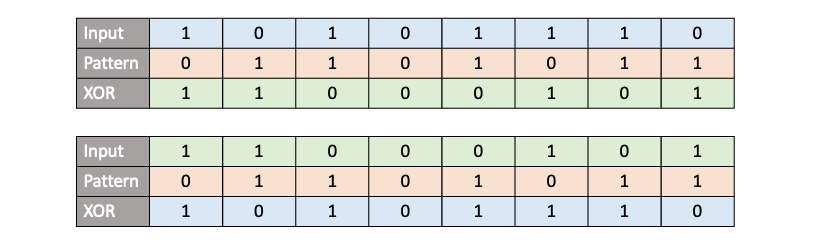

Before we break it, we have to understand why it’s used. The XOR operator (⊕) follows a simple set of rules based on binary bits:

0 ⊕ 0 = 0, 0 ⊕ 1 = 1, 1 ⊕ 0 = 1, 1 ⊕ 1 = 0

The bitwise XOR has a incredible feature ‘involution‘ which means the function is an inverse of itself. So if we have an input bit array, and we apply a XOR operation to it with a key, we get an output. Now if we take the output and XOR it with the original key again, we get back the input. This bidirectional nature makes it convenient for cipher algorithms.Before we break it, we have to understand why it’s used. The XOR operator (⊕) follows a simple set of rules based on binary bits:

1. The Mathematical Erasure of the Key

To understand why a large key doesn’t help, we have to look at the algebra of the XOR operation (⊕). Let’s say we have a massive, non-repeating shared secret (K). We use it to encrypt two different plaintexts (P1 and P2) of the same length.

An attacker intercepts both C1 and C2. They don’t have K. However, they can perform a simple operation: XOR the two ciphertexts together.

Because the XOR operation is commutative and associative, and because any value XORed with itself is zero (K⊕K = 0), the equation simplifies to:

This is the “Equation of Doom.” The key, no matter how long or complex it was, has been mathematically deleted from the equation. The attacker is now holding the XOR sum of two plaintexts. While this isn’t immediately readable as English, it is a catastrophic leak of information.

2. The "Crib-Dragging" Attack

How does an attacker turn P1⊕P2 into actual sentences? They use a technique called Crib-Dragging.

A “crib” is a small piece of known or suspected text. In English, common cribs include ” the “, ” that “, ” and “, or common protocol headers like “HTTP/1.1” or “FROM: “.

The Mechanics of the Drag

The attacker takes a common word like ” the ” and XORs it against the beginning of P1⊕P2.

If the result is gibberish, ” the ” was not at the start of P1.

The attacker “drags” the crib one position to the right and XORs again.

They repeat this until the result looks like a fragment of English.

For example, if the result of (P1 ⊕ P2) ⊕” the “ yields ” meet”, the attacker has just discovered that P2 contains ” meet” at that exact position, and P1 likely contains ” the “.

The Domino Effect

Once a single fragment is found, the rest of the message falls like a house of cards. If you discover P2 says “meet at the…”, you can guess the next word is probably “park,” “airport,” or “bridge.” You XOR your new guess against P1⊕P2 to see what P1 reveals. Because human language is highly predictable and redundant, this process is incredibly fast.

3. Statistical Analysis: The Space Character

Even without a manual crib, the space character (0x20 in ASCII) is the ultimate traitor in XOR encryption.

In English text, spaces occur frequently. When you XOR a space with an alphabetic character, the result is simply the same character with its case toggled (e.g., A ⊕ [space] = a).

If an attacker has several ciphertexts (say, 5 or 6 messages) all encrypted with the same large key, they can look at a single byte position across all messages. If one of those messages has a space at that position, XORing it with the others will reveal the actual letters of the other messages. By looking for the most common “revealed” letters, the attacker can identify where the spaces are and instantly recover the key byte for that position.

4. An Example with Three Sentences

Let’s assume a “very large” shared secret: X7#kL9!pQ2mR5*vB (and so on). We encrypt three messages:

P1: “Deploy the troops”

P2: “Cancel the orders”

P3: “Watch the horizon”

If an attacker XORs C1⊕C2, they get P1⊕P2. Let’s say they guess the crib “the “. They drag it along the XORed sum. At a certain index, they will find that XORing “the ” into the sum produces “the “. This tells them that both messages have the word “the” at that location.

Because the key is reused, the structural similarities of the language (the fact that “the” is used so often) become a beacon. The length of the key provides zero protection against this; it only means the attacker has a longer puzzle to solve, but the puzzle pieces are all provided for them.

5. Another Example with Three Sentences

Using the same “very large” shared secret: X7#kL9!pQ2mR5*vB (and so on). We encrypt three messages:

P1: “The supply truck arrived”

P2: “The unit has enough food”

P3: “We are happy”

If an attacker Looks at first 2 messages and notices that first 4 bits are same, he may guess it is “The “. They will XOR “The” with “4 encrypted bits” to get first 4 bits of the Key. Next they will apply the 4 bit key on P3 to get “We a”, from here they will assume the next word in P3 is “are ” and will XOR “re ” with the next 3 encrypted bits of P3 to get the next 3 bits of the key, which they will apply on P1 and P2. They will get “sup” from P1 and “uni” from P2, from which they will guess the words “supply ” and “unit “.

This way The user can keep guessing the next word in the other sentence with the key broken from the current sentence and come up with the entire shared key.

6. Historical Context: The Venona Project

This isn’t just a theoretical exercise; it has changed the course of history. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union used One-Time Pads that were supposed to be unique. However, due to a manufacturing error, they duplicated thousands of pages of key material.

The US Army’s Signal Intelligence Service (the Venona Project) realized that the “one-time” pads were being reused as “many-time” pads. Despite the keys being completely random and massive in length, the Americans were able to recover significant portions of Soviet diplomatic and intelligence traffic simply by looking for the patterns created by key reuse.

7. How Modern Cryptography Solves This

To use XOR safely, you must ensure that the “key” entering the XOR gate is never the same twice. Modern systems do this using a Stream Cipher or a Block Cipher in Counter Mode (CTR).

The Shared Secret: This is your long-term password.

The Nonce (Number used ONCE): A random value sent in the clear with every message.

The Keystream: The Shared Secret and the Nonce are fed into a mathematical function (like AES or ChaCha20). This function spits out a “Keystream” – a unique, random-looking string of bits.

Because the Nonce changes every time, the Keystream changes every time. Even if you send the exact same message twice, the ciphertexts will look completely different.

Method

Vulnerability

Solution

Simple XOR

Linear relationship between P and C

Frequency analysis / Hamming distance

Large Key Reuse

Crib-dragging / Many-Time Pad attack

Use a unique Nonce

Repeating Key

Frequency analysis / Hamming distance

Use a modern Stream Cipher

Summary

A large key is only a “One-Time Pad” if it is used exactly once. If you reuse a 10GB key to encrypt two different 10GB files, you haven’t created a secure system; you’ve created a 10GB version of the Vigenère cipher. The secret key disappears the moment the ciphertexts are XORed together, leaving the plaintexts to betray one another. In cryptography, uniqueness is often more important than length.

Cheers – Amit Tomar !!