RSA, Shor’s Algorithm, and the Quantum Future

The security of the modern internet rests upon a mathematical “trapdoor” that is easy to enter but nearly impossible to exit without the right key. This trapdoor is the core of the RSA cryptosystem. For decades, it has protected everything from your credit card details to state secrets, under the assumption that classical computers simply cannot factor large numbers efficiently.

However, the dawn of quantum computing has introduced a formidable challenger: Shor’s Algorithm. By leveraging the strange laws of quantum mechanics, this algorithm transforms the “impossible” task of factoring into a manageable calculation.

Part I: The RSA Citadel – How the Trapdoor Works

The RSA (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) algorithm is an asymmetric cryptographic system, meaning it uses two different keys: a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption. Its security relies on the Integer Factorization Problem.

The Mathematical Foundation

To set up RSA, we follow these mathematical steps:

- Select Primes: Choose two very large, distinct prime numbers, p and q.

- Compute the Modulus: Calculate n=p×q. This n is shared publicly.

- Euler’s Totient: Calculate ϕ(n)=(p−1)(q−1). This value must be kept secret.

- Choose an Exponent: Select an integer e (the public exponent) such that 1<e<ϕ(n) and gcd(e,ϕ(n))=1. Usually, e=65537.

- Calculate the Private Key: Find d (the private exponent) such that:

d ≡ e−1 (mod ϕ(n))

In other words, d×e ≡ 1 (mod ϕ(n)).

Encryption and the Trapdoor

When you want to send a message M, you use the recipient’s public key (n,e). The ciphertext C is generated using modular exponentiation:

C = Me (mod n)

To recover the message, the recipient uses their private key d:

M = Cd (mod n)

The Trapdoor Property: If you know p and q, you can easily calculate ϕ(n) and find d. However, if you only know n, you must factor it into p and q. For a 2048-bit number n (roughly 617 decimal digits), a classical supercomputer would take billions of years to find these factors using the best known method, the General Number Field Sieve (GNFS).

Part II: Shor’s Algorithm – Breaking the Trapdoor

In 1994, mathematician Peter Shor realized that while factoring is hard for classical computers, it is just a specific case of a broader problem called Order Finding (or Period Finding). If you can find the “period” of a specific mathematical function, you can find the factors of n.

The Strategy: From Factoring to Periodicity

Instead of trying to divide n by every possible prime, Shor’s algorithm uses a shortcut. Suppose we want to factor n. We pick a random number a that is smaller than n and not a factor of n. We then look at the sequence of powers of a modulo n:

f(x) = ax (mod n)

This sequence will eventually repeat. For example, if n=15 and a=7:

71 (mod 15)

=

7

72 (mod 15)

=

4

73 (mod 15)

=

13

74 (mod 15)

=

1

75 (mod 15)

=

7

The period (or order) r is the smallest integer such that

ar ≡ 1 (mod n). In our example, r=4.

Finding the Factors

Once the period r is known, if r is even and ar/2+1 is not a multiple of n, the factors of n are found using the Greatest Common Divisor (GCD):

For n = 15, a = 7, r = 4:

gcd(74/2 – 1, 15) = gcd(48, 15) = 3

gcd(74/2 + 1, 15) = gcd(50, 15) = 5 We have successfully factored 15.

The Catch: For the massive numbers used in RSA, finding the period r is just as hard for a classical computer as factoring itself. This is where the quantum computer enters the stage.

Part III: How Quantum Computers Speed Up the Process

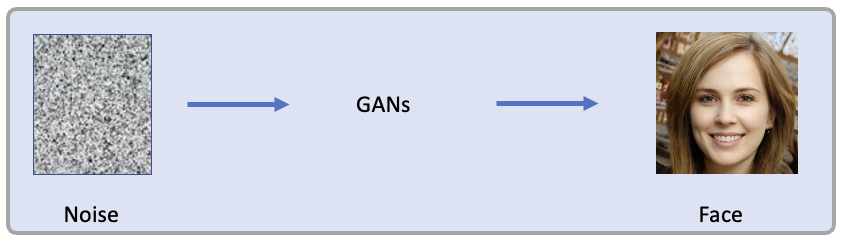

A classical computer must calculate ax (mod n) for x=1,2,3… sequentially until it finds r. A quantum computer uses three “superpowers” to skip this line: Superposition, Interference, and the Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT).

Superposition: Massive Parallelism

In a quantum computer, qubits can exist in a state representing both 0 and 1 simultaneously. If we have Q qubits, we can create a superposition of all possible values of x from 0 to 2Q−1. The quantum computer calculates ax(modn) for all values of x at the same time in a single operation. The state of the computer becomes:

The Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT)

Even though the computer has calculated all values, if we measure it now, the state “collapses” into just one random value of x, giving us no information about the period r. We need a way to extract the global pattern of periodicity without looking at individual values.

The Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT) is the secret sauce. Just as a prism splits white light into its constituent frequencies, or a musician identifies the pitch of a vibrating string, the QFT analyzes the superposition and identifies the dominant frequency—which corresponds to the period r.

Constructive Interference

The QFT works through interference. In the quantum state, the incorrect answers (values that do not align with the period r) undergo destructive interference—their amplitudes cancel each other out. The correct values that point toward the period r undergo constructive interference, reinforcing each other.

When we finally measure the qubits, we are highly likely to see a value that allows us to calculate r almost instantly.

Exponential Speedup

The difference in efficiency is staggering:

- Classical (GNFS): As the number of bits L in the modulus n increases, the time required grows exponentially.

- Quantum (Shor’s): The time required grows polynomially—specifically O(L3).

RSA Key Size

Classical Time (Estimated)

Quantum Time (Estimated)

1024-bit

~2,000 years

~Minutes

2048-bit

~1 billion years

~Hours

4096-bit

~Age of the universe

~Days

The Future: Post-Quantum Cryptography

While Shor’s algorithm is mathematically sound, we do not yet have a quantum computer with enough stable, error-corrected qubits to break a 2048-bit RSA key. Estimates suggest we need roughly 20 million physical qubits; current high-end machines are still in the hundreds.

However, the “Harvest Now, Decrypt Later” strategy—where adversaries save encrypted data today to decrypt it once quantum hardware arrives—has spurred a global move toward Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC). These new algorithms, based on lattice math or multidimensional equations, are designed to be “trapdoors” that even a quantum computer cannot solve.

The transition from RSA to quantum-resistant standards is perhaps the most significant security overhaul in the history of the internet, ensuring that even in a world of quantum super-intelligence, our secrets remain secret.

Cheers – Amit !!